| Washington Post article

The Washington Post carried the following article on December 29, 2003.

|

|

The Summit of Their Joy

Making Memories to Share On the

Appalachian Trail

By Bob Bridges

Special to The Washington Post

Monday, December 29, 2003; Page C10

|

|

When men reach a certain age, they inevitably ask themselves the question, “Is there something better

out there I’m missing?” Call it the seven-year itch, call it midlife crisis, or the alpha male

competition; nonetheless, it’s this devilish little voice that supports Ferrari dealerships, divorce

lawyers, and a host of other odd societal conventions.

The voice came on one of those muggy, steamy Washington afternoons – the type with air so thick you

can barely see a dozen cars ahead on the beltway. I dreamed of solitude, of indigo skies seen from

mountain peaks, of hiking atop the world, with no cares or fixed schedule, all my earthly belongings

within my backpack. It was settled – I’d fly out to the Canadian Rockies for a week of backpacking

and return refreshed and empowered. At least so I thought until I advised my wife Coleen, whose

response proved wholly uncharacteristic.

“Not without me you’re not” – no debate, no negotiations.

It was an unexpected setback, but the little voice within me still demanded an answer. After all,

we’d married later than most, and though we’d both traveled the world; most of our adventures had been

separate. We needed some shared memories, a goal we could pursue together, a chance to stand

shoulder-to-shoulder against the odds.

We needed the Appalachian Trail.

Completed in 1937, this 2,171-mile trail from Georgia to Maine is a slice of Americana popularized in

Bill Bryson’s 1996 comic bestseller, “A Walk in the Woods.” Each spring, over 2,000 hikers leave its

southern terminus at the remote Mount Springer bound for the impossibly distant Mount Katahdin in

Maine – although only one in eight will complete their pilgrimage, all will be irrevocably changed.

Our jobs couldn’t accommodate the six months needed to hike it in one summer, but we could

“section-hike” the trail, hiking in week-long intervals of about 75 miles each.

|

|

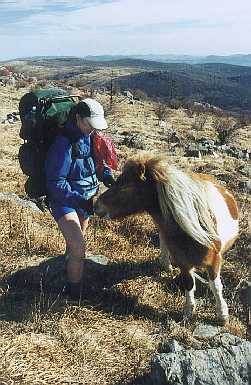

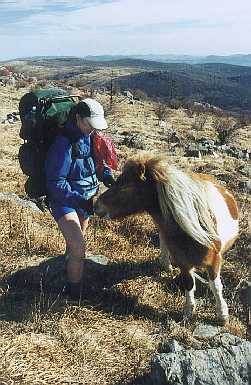

| Coleen feeds a wild pony in southwest Virginia

|

|

And so it was that we climbed into a sea of cloud atop Mt. Springer four years ago - the day of our

15th anniversary. We were tenderfeet in every sense of the word, giddy with excitement as we began,

but reality lapped at our heels. Around the campfire the wind rose as the clouds covered the moon,

and by midnight the downpour began in earnest – a deluge that was to continue all of the following day

and night. We awoke on Thanksgiving morning to a cold, driving rain, knowing that our friends,

family, and most of the civilized world were warm, entertained, and well-fed.

Hiking in the rain is nothing short of miserable – no matter how good one’s gear, the rain and sweat

eventually overcome all. Wet socks reduce the feet to hamburger, and even the smallest chore –

looking at a map, or fishing for a granola bar – soaks any previously dry items. The mountain winds

pelt the rain against our hoods with a mind-numbing din, and the “spectacular overlooks” are limited

to a few yards into a gray. That night, we erected our tent in the inky blackness of a briar patch

(the only level ground to be found), the rain washing bloody streaks across our thorn-torn legs. We

wanted to quit.

But the next day brought our deliverance – the skies cleared and a glorious sun appeared, the trail

leading to the dazzling overlook from Blood Mountain. Better yet, from here it descended to Neels

Gap, the first major oasis of civilization on the trail, where the eternal quest for town food and ice

cream could be satisfied (though historically almost a third of all hikers drop out here). We managed

to secure a nearby cabin for the night, drying our gear and living in the lap of luxury – the Waldorf

Astoria wouldn’t have suited us any better.

Such is the A.T. – the best of times, the worst of times. The challenges are legion – blisters,

bears, endless climbs, ice-covered descents, raging rivers to ford, and singularly foul T-shirts. But

its delights are every bit as real – often as simple as finding a clear, cold spring - others so

spectacular as to defy words and bring tears to our eyes.

|

The A.T. is a very social trail, filled with hikers of all ages, nationalities, and motivations. In

fact, the 7,000 hikers who have completed it include several octogenarians, the blind Bill Irwin, and

Scott Rimm-Hewitt, carrying his tuba "Charisma" the entire length (he credits it with saving his life

during one tumble from a Pennsylvania cliff, its crumpled bell protecting his head from the rock

beneath). Many are fresh out of college, still unsure the direction their life will take. Yet we all

share one absolutely universal passion – food. We fantasize about it around the campfire, we dream of

it at night, and we hike miles off the trail in search of Ben & Jerry's.

We were quickly becoming veterans, with well over a thousand miles of trail to our credit. We’d seen

the bears and the rattlesnakes. We’d hiked in all seasons through every kind of weather - knee-deep

snow, stinging sleet, lightning arcing between cragged peaks, and rain lasting weeks on end. We’d

slept everywhere imaginable – barns, open fields, cliffs, one jailhouse, and a monastery. We knew

everything there was to know about the trail.

Then came the Whites.

The moment we climbed into New Hampshire’s White Mountains, we knew we’d jumped into the deep end of

the pool. Our initiation occurred on Franconia Ridge, just after a cold front passed, leaving winds

gusting to 83 mph. Try to imagine standing erect in winds of this magnitude; then add a

backpack-shaped appendage, and a treadway composed of large, jagged rocks. Three days later we’d

summit Mt. Washington, home to the world’s worst recorded weather, including a surface wind speed of

231 mph measured here in 1934. On our summit day, the wind relaxed to a modest 50 mph, although the

50 foot visibility gave the eerie sensation of hearing the whistling of approaching buildings before

seeing them.

We were being tried severely, but with each trial came the sense of conquest – we might just make it

to Maine. And we’d often find the harshest of terrain hand-in-hand with unparalleled beauty, a

combination that would continue well into the rugged Maine landscape. Our cup of memories was

brimming.

|

|

But the real crown jewels of the A.T. were the people we’d encounter – a 2000-mile community possessed

of unbounded hospitality. The tradition of “trail magic” always seemed to appear just when we needed

it most – water jugs by the road crossings when the springs were dry, a few soda’s left in a cold

stream, a hitch when we really needed a “town night”.

And we’d find our fellow hikers no less generous – the “dog-eat-dog” world within the

beltway was far behind us now. We entered the legendary "100-mile Wilderness" in Maine on October 5

with thirteen such hikers, each of us hastening to close out this final chapter of our quest before

the winter snows closed the trail. They were typical of those we'd hiked with the previous four years

- most far younger than us, many with no idea where the next month would take them. Our backgrounds

and motivations couldn’t have been more diverse, yet we shared a powerful sense of community. We were

a band of brothers, each ready to sacrifice greatly for the other, and each going to sleep at night

dreaming of a mountain called "Katahdin."

The dream became reality at 10:12 am, Sunday, October 12.

Katahdin is by far the toughest climb on the A.T. – we were battered and weary, yet exhilarated at our

entry into the Promised Land. As we approached the summit, here was our troop atop, cheering us on –

and like many of the others, Coleen broke into tears as she climbed to touch the sign. It was a

bittersweet moment – the thrill of the victory, but the end of a chapter of our lives we’d trade for

no other.

The cheers and the tears will reside with us forever.

--------------------------

Bob and Coleen Bridges live in Northern Virginia. Their hiking journals may be found online at

https://trailtales.tripod.com/ .

|

|

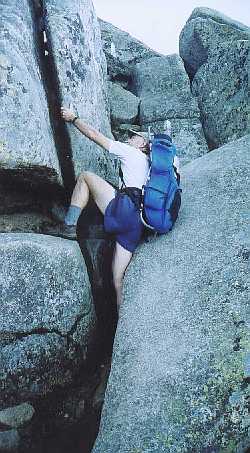

| The Promised Land |

| |